Battle of Cloyd's Mountain

| Battle of Cloyd's Mountain | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Crook-Averell Raid (a.k.a. Dublin Raid) on the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad of the American Civil War | |||||||

Pulaski County, Virginia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

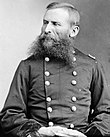

| George Crook |

Albert G. Jenkins † John McCausland | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~ 6,555 | ~ 2,350 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

688

|

538

| ||||||

The Battle of Cloyd's Mountain occurred in Pulaski County, Virginia, on May 9, 1864, during the American Civil War. The fight has also been called the Battle of Cloyd's Farm. A Union Army division led by Brigadier General George Crook defeated a Confederate Army consisting of three regiments, one battalion, and Confederate Home Guard. The Confederate force was led by Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins and Colonel John McCausland. Although the intense fighting portion of this battle may have lasted for only one hour, it was southwestern Virginia's largest fight of the Civil War.

The battle was a Confederate attempt to prevent an attack on the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad. That railroad was important to the Confederacy for moving troops and supplies. The fighting occurred about five miles (8.0 km) north of the Virginia & Tennessee's Dublin Depot. Additional Confederate forces arrived at a nearby railroad depot after the major portion of the fighting was completed, and they enabled the Confederate fighters to escape.

On the next day, skirmishing erupted at a Virginia & Tennessee Railroad bridge located about eight miles (13 km) east of the Dublin Depot. This fighting was essentially an artillery duel, and its few casualties are included in totals for both sides. Confederate forces eventually fled further east, and the railroad bridge was burned by Crook's men. Although Union forces burned the railroad depot, burned a major railroad bridge, and destroyed portions of the railroad track, the damage was repaired in about one month.

Background

[edit]During March 1864, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant became commander of all Union armed forces.[1] Grant's strategy in Virginia was to attack the strongest Confederate Army, Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, from multiple fronts.[2] The Union's Army of the Potomac would target Lee's army directly, while another Union force would attack Lee and the city of Richmond from the east.[3] In western Virginia, the railroads that supplied Lee's army were Union targets, including the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad and the Virginia Central Railroad.[4] Each of those two railroads also had more mileage within Virginia than any other railroad.[5] Attacking the railroads would cause Lee to send troops west to protect vital railroad infrastructure, resulting in fewer men available to protect the Confederate capitol in Richmond.[4]

Grant's plan

[edit]In 1860, there was more railroad track in the United States than all other countries combined. The American Civil War became the world's first war where railroads played an important part. While the Union states had much of the railroad milage, the Confederate States still had more mileage than any other country. Railroads carried troops, food, supplies, and raw materials.[6]

Grant ordered Major General Franz Sigel to advance south in the Shenandoah Valley to Staunton, Virginia.[7] The Virginia Central Railroad ran through Staunton and connected with Richmond.[8][Note 1] Sigel began his part of the plan on April 29, and he departed from Martinsburg, West Virginia.[10] Grant ordered Brigadier General George Crook to attack the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, including its bridge over the New River. From there, Crook would form a junction with Sigel at Staunton and advance to Lynchburg.[11] Crook began making preparations in Charleston, West Virginia. By the end of April his troops were assembled further south in Fayetteville, and they began moving toward their destination on May 3.[12]

Crook took an infantry division and began moving toward the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad's Dublin Depot. He sent a smaller 2,500-man cavalry force, commanded by Brigadier General William W. Averell, to attack further west from Crook's destination.[13][Note 2] Averell's goal was to disable a salt works located in a town called Saltville.[13] After 1863, this salt works produced an estimated two thirds of the salt used by the Confederacy.[15][Note 3] A potential target for Averell was the Austin lead mine located south of Wytheville in Wythe County. The lead mine produced about one-third to one fourth of the lead consumed by the Confederacy.[17]

Virginia and Tennessee Railroad

[edit]

The Virginia & Tennessee Railroad was 204 miles (328 km) long and connected Lynchburg, Virginia, to Bristol at the Virginia–Tennessee border.[18] Additional railroads could be used from Lynchburg to move east to Richmond, and railroads connecting to Bristol could be used to move west to Knoxville, Chattanooga, Memphis, and Corinth.[19] The Virginia & Tennessee carried Confederate soldiers and raw materials both east and west.[15][Note 4] The railroad was also an important transporter of food from southwest Virginia to soldiers and civilians in the east.[20] President Abraham Lincoln called the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad the "gut of the Confederacy".[21]

In western Virginia, a branch line of the Virginia & Tennessee ran north from Glade Spring to a salt works in Saltville, Virginia.[17] Further east along the line were lead mines located south of Wytheville.[22] Further east from Wytheville was the regional Confederate Army headquarters at the Dublin Depot just north of Newbern, Virginia.[23] Dublin was also the home of an instruction camp for Confederate recruits, and it was the commissary and quartermaster center for southwestern Virginia.[24] East of the headquarters was a large railroad bridge across the New River.[25] The bridge was 780 feet (240 m) long, and it was constructed with timber on stone pylons.[26] Grant regarded the railroad as "one of the most important lines connecting the Confederate armies".[11] Several attacks on the railroad in 1863 had only limited success.[27][Note 5] When Grant met with Crook in March, he emphasized that he wanted the railroad's infrastructure destroyed in multiple places.[11]

Opposing forces

[edit]Union force

[edit]

Crook's force was the 2nd Infantry Division of the Department of West Virginia.[29] It was also known as the Kanawha Division.[30] The division consisted of three brigades of mostly infantry, plus two batteries, that totaled 6,155 men.[31] Crook was experienced and his men were confident in his abilities.[32] A 400-man detachment of cavalry was added to his 1st Brigade while they were preceding to their target destination, which increased the size of the force to 6,555.[31]

- 1st Brigade - This brigade was commanded by Crook's best commander and a future president of the United States, Rutherford B. Hayes.[33] The brigade's 23rd Ohio Infantry included another future president, William McKinley.[34] Another regiment in the 1st Brigade, the 36th Ohio Infantry, had fought under Crook's command in 1862 in the Battle of Lewisburg.[35] The 400-man cavalry detachment added to the brigade was essentially mounted infantry, and it was not armed with sabers.[36]

- 2nd Brigade - Commanded by Colonel Carr B. White and consisted of four infantry regiments.[31] White was responsible for creating Blazer's Scouts, an "elite group of commandos".[37]

- 3rd Brigade - Commanded by Colonel Horatio G. Sickel and consisted of four regiments.[31]

- Artillery - Captain James R. McMullin was the Chief of Artillery for two batteries.[38] The combined firepower of the two batteries was 12 artillery pieces.[13]

Confederate force

[edit]

Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins was temporarily in command of the Confederate Department of Western Virginia.[39] Jenkins had very few soldiers readily available, and nearly all Confederate participants in the battle either arrived at the Dublin Depot by railroad or were delayed from departing from Dublin on the railroad.[40] Approximately 2,350 men were under Jenkins' command for the battle, and he had ten artillery pieces.[41][Note 6] All three regiments at Cloyd's Mountain, and Colonel John McCausland, had gained experience in 1862 when they fought in the Kanawha Valley Campaign. One of the regiments had also fought against George Crook in the Battle of Lewisburg.[42]

- 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment - This regiment was commanded by Colonel William H. Browne.[43]

- Fourth Brigade - This brigade was commanded by Colonel John McCausland. It consisted of the 36th and 60th Virginia Infantry Regiments, the 45th Battalion Virginia Infantry (a.k.a. Beckley's Battalion), and Bryan's artillery battery.[44]

- Ringgold Battery - This artillery battery was commanded by Captain Crispin Dickenson. It had four artillery pieces: three 12-pounder Napoleons and one 3-inch rifled gun.[45]

- Home Guard - Captain White G. Ryan commanded the Montgomery Home Guards.[46] Other volunteers included James Cloyd, owner of Cloyd's Farm; and Reverend William P. Hickman of the Dublin Presbyterian Church.[47]

Prelude to Battle

[edit]Crook begins

[edit]

In addition to sending Averell's cavalry to Saltville, Crook had additional plans to confuse the Confederate Army. He sent the 5th West Virginia Infantry, led by Blazer's Scouts, east on the Kanawha Turnpike toward Lewisburg. The infantry band played during the march, and at night huge bonfires burned.[48] This deception worked, causing Confederate leadership to believe that an entire division was moving toward Lewisburg.[3]

Crook's main force began moving on May 2 and marched south toward Raleigh Court House (Beckley).[49][Note 7] The major difficulty in the march was cold and wet weather plus trees that had been chopped down to obstruct the roads. Crook took steps to conceal his movement. A small cavalry force led the expedition, and videttes rode on the main force's right and left to prevent bushwhacker/snipers from harassing the troops. Trees were burned as the troops moved over the mountains to provide a smokescreen that concealed the size and movement of Crook's force.[51][Note 8]

Breckinridge reacts

[edit]Confederate Major General John C. Breckinridge was commander of the Department of Western Virginia and headquartered in Dublin on the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad.[54] He had been appointed to this position earlier in the year. A former vice president of the United States in the James Buchanan administration, he was experienced and skilled in military affairs. His department was responsible for all of Virginia west of the Blue Ridge Mountains and south of Staunton, the southern portion of West Virginia, and eastern Tennessee.[55] He did not have enough troops to protect his vast and mountainous territory.[56] His priorities were to protect the Saltville salt mines, the Austinville lead mines, and the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad.[57]

On May 1, Lee informed Breckinridge that it appeared that Union troops commanded by Averell were planning to attack Staunton (Virginia Central Railroad) or the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad. Lee mistakenly thought that Staunton was the main target, and movements further west were deceptions.[58] Brigadier General John H. Morgan and his brigade were relieved from duty in eastern Tennessee and ordered to report to Breckinridge.[59] Breckinridge shifted the few troops he had in response to reports that Saltville and the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad were the Union targets.[60]

Davis and Lee change Breckinridge's priorities

[edit]In correspondence dated May 4, Breckinridge was told by Confederate president Jefferson Davis to communicate with General Lee and protect Staunton against Sigel's army advancing south in the valley.[61][Note 9] Breckinridge began moving most of his troops to Staunton via the Virginia Central Railroad's western terminal at Jackson River Depot.[23][Note 10] An exception was the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment, which was stationed in Saltville, Virginia. The movement of troops toward Staunton left the territory west of the New River and east of Saltville with little protection.[66] Brigadier General Albert G. Jenkins was left behind with the small command of scattered troops.[61]

Crook moves closer

[edit]

McCausland's Brigade left Princeton on May 5 to begin its move to Staunton. When Crook's Union infantry arrived at Princeton on May 6, he encountered a small cavalry company that fled after token resistance—instead of an entire brigade.[67] After capturing the town, Crook's men camped overnight, and departed on the next day at 4:00 am. Crook had two choices for his route to the railroad. He believed that the most direct route might be guarded, so he took an indirect route on a rougher road through the mountains and Rocky Gap.[68]

The Union capture of Princeton worried Confederate leadership because the town was considered an important point for guarding major roads west of the New River that lead to the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad, including the salt works and lead mines.[39] Jenkins grew more concerned—he had only 200 fighters. He requested that Breckinridge allow McCausland's Brigade to remain with Jenkins for a day or two longer.[69][Note 11] On the evening of May 6, McCausland stopped his men from boarding the train in Dublin. He removed his artillery from the train and made camp at Dublin.[71]

Troops are positioned

[edit]Confederate positions

[edit]

On May 7, Jenkins moved his headquarters from the Narrows to Dublin Depot. He decided he would intercept Crook on the Dublin–Pearisburg Pike at Cloyd's Farm.[72] This site is at the base of the south side of Cloyd's Mountain. To get to Jenkins' men, Union soldiers would have to descend the south side of the mountain and cross an open area with a creek known as Back Creek.[73] There had been some debate on placing artillery on top of the mountain and blocking the road, but others worried about losing cannons from a flanking maneuver.[74]

In addition to having McCausland's Brigade, Jenkins pulled the Ringgold Artillery Battery from the train in Dublin. This battery was sent on May 7 to a series of bluffs south of Cloyd's Mountain where they could cover the Dublin–Pearisburg Turnpike.[75][Note 12] McCausland deployed his brigade at Cloyd's Farm early on May 8, and began construction of fortifications early in the morning on May 9.[77] Home guard such as the Montgomery Home Guards and volunteers from Christiansburg and Dublin were also deployed.[46]

Early in the morning on May 8, the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment left Saltville to reinforce Jenkins. They reached the base of Cloyd's Mountain at 9:00 am on May 9.[43] Inspecting McCausland's deployment, Jenkins made some changes in the positioning of the men.[78] The front line consisted of the 60th Virginia Infantry on the left, one artillery piece, Home Guard in the middle, and the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment on the right. Further back on the far left was Bryan's Artillery Battery supported by the 36th Virginia Infantry. On the far right behind the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment was the 45th Virginia Infantry Battalion (a.k.a. Beckley's Battalion), and it protected the Confederate right flank along a wooded area.[79] A cavalry detachment of about 750 men from Brigadier General John H. Morgan's command was supposed to leave Saltville on May 8 by train. Equipment problems caused the train to not leave until close to midnight on May 8, and many men had to be left behind at Glade Spring. The detachment was commanded by Colonel D. Howard Smith, and only 400 men made the entire trip. On the morning of May 9 they were still en route.[80]

Union positions

[edit]

Crook's troops camped on Wolf Creek during the night of May 7. On the next day, they marched 24 miles (39 km) along the creek until they reached Shannon's Bridge and camped for the evening. The bridge was located at the junction of the Giles Court House (Pearisburg), Princeton, and Dublin roads. It was about 10 miles (16 km) from Dublin Depot. At that time they were joined by a detachment of 400 cavalrymen led by Colonel John H. Oley. Crook believed that Confederate troops would be waiting for them at the summit of the mountain on the road to Dublin, and more Confederate soldiers would be waiting on the south side.[81] Crook's men began moving toward the mountain at sunrise on May 9, and skirmishers were driven away from the summit.[82] All Union forces had reached the summit by 9:00 am, and they were greeted by Confederate artillery fire.[83]

In the woods near the bottom of the mountain, Crook sent Sickel's 3rd Brigade to Jenkins' left (Crook's right) where they formed a battle line close to the road.[84] Sickel's report said his men were placed at 11:00 am.[85] White's 2nd Brigade was covertly placed on Jenkins' right under the cover of a wooded-area. Hayes' 1st Brigade, with Crook, formed in between the 3rd and 2nd Brigades.[84] The cavalry attached to the 1st Brigade remained back "a mile or two" (1.6 to 3.2 km) protecting the rear and guarding the wagon train.[86] Crook's artillery began returning artillery fire not only at the Confederate artillery, but also at the Confederate fortifications.[84] About 100 men from the cavalry in the rear guard moved forward and dismounted to protect two of the artillery pieces.[86]

Battle

[edit]Confederate right

[edit]

Crook ordered Colonel White, commander of the 2nd Brigade, to find Jenkins' right and strike hard.[84] The three Union brigades were supposed to simultaneously attack on the left, right, and center. White was expected to wait for a signal cannon, but he could not distinguish the signal cannon from the artillery duel already in progress—so he attacked prematurely.[87] White used the 14th West Virginia Infantry and the 12th Ohio Infantry to attack Jenkins' right.[88] Both regiments were repelled after 20 to 30 minutes of fighting.[89] The Union soldiers made the mistake of halting in the open to return fire to an enemy behind fortifications.[90] According to the report of Colonel Daniel D. Johnson, commander of the 14th West Virginia, the Confederate infantrymen were so well protected by a breastworks composed of logs and fence rails that fire from the guns could be seen—but no soldiers.[91]

Observing the Union retreat, Jenkins ordered Beckley's men, with support from two companies of the 45th Virginia Infantry, to counterattack. He also ordered two artillery pieces moved from his left side of the battlefield to the right. Because of the woods and brush, Jenkins did not know that the 9th West Virginia and 91st Ohio Infantries were waiting behind a ridge in back of the two attacking regiments.[88] Beckley's men were surprised with a volley from the two Union regiments.[92] Fearing that his men would be surrounded, Beckley ordered a retreat to his original position.[93] After the two Union regiments involved in the initial attack were safely in the rear, the other two Union regiments charged.[88] By this time, Beckley's men began panicking, which caused them to retreat in confusion.[94] The Union charge was blunted by the arrival of the two Confederate artillery pieces.[88]

Confederate left and center

[edit]

Sickel's Brigade began moving after the 2nd Brigade attack, but before the 1st Brigade was finished positioning.[95] According to Sickel's report, his 3rd Brigade "was ordered to advance upon the enemy's works" at about 12:00 am.[85] Sickel's men charged across a meadow against an enemy (60th Virginia Infantry) protected by fortifications. Bryan's Confederate battery (from the distant left) responded with canister, and soon Sickel ordered a retreat.[88] Sickel's Brigade had about 100 casualties in only a few minutes—including the commanding colonel of the 4th Pennsylvania Reserves.[96] For a moment, the Virginians thought they had won the battle—until they saw on their right Union troops about to flank them.[88]

Hayes' 1st Brigade, consisting of infantry from Ohio, began their advance after the 3rd Brigade. Confederate home guard and the 60th Virginia Infantry, unaware of the situation on their extreme right, left their fortifications to meet Hayes' men. Unlike the other two brigades that paused to fire volleys at an enemy behind fortifications, the 1st Brigade rarely stopped moving. Moving with the brigade near the front was Brigadier General Crook, who was dismounted. After a brief pause, the brigade charged the final 250 yards (230 meters) up some bluffs where they ran directly into the 60th Virginia. They fought for about 20 minutes.[97] The Confederate line broke and men began fleeing in confusion.[98]

Confederate right flanked

[edit]

When Hayes made his charge, he had his left wing unite with White's 9th West Virginia. At the same time, the 91st Ohio moved around the Confederate right flank and began firing into the Confederate rear.[98] Jenkins was wounded in the arm around this time, and he turned over command to Colonel John McCausland. The new Confederate commander immediately moved one artillery piece and the 36th Virginia Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Smith, from the left to the right. The 36th Virginia formed two lines about 200 yards behind the Confederate line on the right. They slowed the Union advance, and McCausland ordered a charge against the 91st Ohio.[98] After Smith was wounded, many from his command fell back. They were soon joined by Beckley's Battalion.[99]

In danger of being surrounded by the Union's 9th West Virginia and 91st Ohio, the 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment needed to link with the 60th Virginia.[99] Leading two companies from the 60th Virginia, Major Jacob N. Taylor was killed in action. Lieutenant Colonel E. H. Harman, who was commanding the left wing of the 45th Virginia Infantry, was mortally wounded shortly after the link up.[43] Using one piece of artillery, the 45th Virginia was able to escape from being surrounded, although that piece was captured. As the Union troops pursued them, another cannon (a 12-pounder Napoleon) fired grape and canister until no Union soldiers were standing.[100] At that time, the artillery crew began retreating with everyone else.[99] On the far left, Bryan's Battery was receiving Union artillery fire from two locations, and it could not help the Confederate infantry because they were mixed with the Union soldiers. With little infantry support, the battery was threatened by the 15th West Virginia Infantry, and it was eventually forced to join the retreat.[99]

Confederate retreat

[edit]

McCausland reformed the 36th Virginia (with remnants of other units) for the purpose of delaying the Union pursuit, and he was assisted by one of the artillery pieces from the Ringgold Battery. For the pursuit, Crook brought forward the few cavalrymen he had.[101] Colonel John H. Oley commanded the cavalry detachment that consisted of portions of multiple regiments with horses that were not in good condition.[102][Note 13]

Unknown to the Union soldiers, the detachment of Confederate men from Morgan's command arrived at Dublin by rail when the battle was almost over. The commander of the detachment, Colonel D. Howard Smith, immediately moved his men toward Cloyd's farm. Before they had advanced very far, they met Colonel McCausland and retreating Confederate soldiers. McCausland had Smith place his men near the road to protect the retreat, and they were initially effective in stopping the Union pursuit. After about one hour, Smith found his men in danger of being flanked, so they also began a slow retreat. Smith's force joined McCausland's men that evening around sunset.[103]

The delaying action by the 36th Virginia, and then Morgan's detachment, enabled McCausland to evacuate Dublin and move troops, artillery, and a portion of Dublin's supplies eight miles (13 km) east to the New River railroad bridge.[104] Waiting to assist McCausland on the west side of the bridge was the Botetourt Artillery, which did not fight in the battle at Cloyd's farm.[105] The west side of the bridge had some defensive works that were not entirely completed, but McCausland believed his men could be trapped by the river if they tried to defend from that side. He had his men cross the bridge to the east side, and it took five hours to move six pieces from the Botetourt Artillery across the river by boat.[106]

Crook in Dublin

[edit]When Crook's men entered the Dublin Depot, they found some telegraph dispatches (possibly planted) that incorrectly indicated Grant had been repulsed and was retreating in eastern Virginia. Communications between Dublin and Lynchburg also caused concern about Sigel's portion of Grant's plan to attack Staunton—and Crook had heard nothing from Sigel. Crook was now about 150 miles (240 km) beyond his base and low on food and ammunition. If Grant and Sigel had been repulsed, more Confederate troops would be available to pursue Crook. For that reason, Crook believed it would be prudent to return north to Lewisburg. This would put his command close to his supply base, but still keep him in position to join Sigel at Staunton (as planned) if Sigel had been successful.[107]

In Dublin, Crook's men found warehouses with food, military equipment, and tobacco. They camped in Dublin that night, and began destroying anything of military value in the morning. Buildings burned included the depot and adjacent property, warehouses, a nearby hotel, and one or two private residences. They also destroyed part of the railroad line. About six miles (9.7 km) of railroad track and ties were removed from the line. The track was made useless heating it with burning railroad ties and twisting it.[108]

New River bridge

[edit]Approaching the railroad bridge on May 10, Crook's men drove off skirmishers. At 9:30 am Crook's artillery began firing at the Confederates on the other side of the river, and Confederate artillery returned fire. The exchange of artillery fire lasted for about three hours. The Union artillery had an advantage of being mounted on a higher elevation. Two guns from Union Captain David W. Glassie's 1st Kentucky Battery were able to hit the railway roundhouse at the railroad's Central Depot, which was about one mile (1.6 km) away. Captain James R. McMullen's 1st Ohio Battery put two Confederate guns out of commission.[109]

Believing that a Union infantry force had crossed the river at another location in an attempted flanking maneuver, McCausland withdrew toward Christiansburg. The Union soldiers pushed two burning railroad cars onto the bridge, causing the bridge to burn down. It took two hours to burn, and all that remained were the bridge's pylons.[110] Although McCausland believed he would be pursued further east, Crook chose not to do so. Crook had already accomplished his goal of destroying Dublin Depot, the bridge, and some track. Instead, he decided to move back to West Virginia.[111]

Aftermath

[edit]

Averell's cavalry was unable to attack the salt works or lead mines, and was repelled in the Battle of Cove Mountain on May 10. He arrived in Dublin on May 11 after Crook had left for the New River Bridge. Both Crook and Averell planned to move back to the security of West Virginia.[112] Averell left Dublin on May 12 and proceeded toward Christiansburg, where he destroyed more railroad infrastructure and military supplies. He then moved back toward West Virginia.[113]

Crook took a different route to West Virginia, but the two Union forces joined at Union, West Virginia, on May 15. Their journey ended on May 19 when they reached a Union camp at Meadow Bluff, West Virginia.[113] Both Crook and Averell had been unsuccessfully pursued by Colonel William H. French's 17th Virginia Cavalry and Colonel William L. "Mudwall" Jackson's 19th Virginia Cavalry.[114]

Result and casualties

[edit]Discounting early skirmishing and the pursuit, estimates of the duration of the main portion of the battle range from slightly less than one hour to 90 minutes.[115] The battle was a victory for Crook and the Union army. Confederate Colonel McCausland described the result by simply saying "We were defeated".[116] Despite driving the Confederate Army off the battlefield, capturing Dublin Depot, and burning an important railroad bridge, Crook did not achieve total victory because the Confederate Army was able to get away.[117] Crook did not have explosives necessary to destroy the foundation of the New River bridge. It was rebuilt, using fire-resistant green timber, in less than five weeks.[118]

Union casualties listed in Crook's report, which include the skirmishes on May 8 and 10 (New River Bridge), totaled to 688. Carr's 2nd Brigade had 391 of the casualties, which included 186 for the 9th West Virginia.[119] The total casualties of 688 amounted to roughly 10 percent of the Union force.[120] The 5th and 7th West Virginia cavalry detachments had no casualties listed despite a regimental history describing "riderless horses" and McCausland reporting them "repulsed with considerable loss".[121]

Brigadier General Jenkins did not recover from the wound to his arm. He was captured and treated at the Cloyd house, but an improper treatment of a ligature caused him to bleed to death on May 21.[120] Confederate casualties totaled 538 in McCausland's report. He called the fight "the battle of Cloyd's Farm", and his casualties included the battle of May 9 and subsequent operations. The 45th Virginia Infantry Regiment and 60th Virginia Infantry accounted for 174 and 158 of the casualties, respectively. Also included in the total was one casualty for the Botetourt Artillery—which fought on May 10 at the railroad bridge, but not on May 9.[122] The 17th Virginia Cavalry, which was not present for the fighting on May 9 or May 10, had two casualties listed. It was involved in the pursuit of Crook's and Averell's forces.[123] Although Confederate casualties were lower than those of the Union, they accounted for nearly one quarter of their strength.[120]

Results for Grant's plan

[edit]Grant and the Army of the Potomac fought Lee's Army of Northern Virginia on May 5 through May 7 in the Battle of the Wilderness. The battle was inconclusive, but Grant continued toward the Confederate capital city of Richmond instead of retreating like his predecessors.[124] Despite Averell's lack of success with the mines, he diverted Confederate troops away from Crook.[125] Breckinridge defeated Major General Franz Sigel on May 15 in the Battle of New Market, and this caused Sigel to retreat north.[126] Six days later, Sigel was replaced by Major General David Hunter.[127]

Notes

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The Virginia Central Railroad was 200 miles (320 km) long and connected Richmond, Virginia, with the upper Shenandoah Valley. The railroad had been used by Lee and Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson to move troops in the 1862 Valley and Peninsula Campaigns. It was also used to move agricultural products and raw materials from the Shenandoah Valley to Richmond.[9]

- ^ Some historians, including Patrick K. O'Donnell and Richard R. Duncan, call Crook and Averell's May 1864 attacks on the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad "the Dublin Raid".[14]

- ^ Salt, an essential part of the diet for humans and livestock, was also used for packing and preserving meat during the American Civil War.[16]

- ^ An example of Confederate troops using the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad for transportation is the 1863 transport of a portion of Lieutenant General James Longstreet's First Corps from Lee's Army of Northern Virginia to Tennessee where it reinforced the Confederate Army in the Battle of Chickamauga.[15]

- ^ An attack on the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad and lead mines near Wytheville, Virginia, known as the Wytheville Raid, was made during July 1863 and caused only minor damage to the railroad.[28] Brigadier General Averell led attempts to damage the railroad in November and December 1863. These actions became known as the Battle of Droop Mountain and the Salem Raid.[27]

- ^ Dr. Richard C. Whisonant uses a count of 2,400 men available for Jenkins.[13]

- ^ At the time of the American Civil War, some of the small county seats (especially in Virginia) were identified with the county name followed by "Court House". For example, Beckley, Virginia (later Beckley, West Virginia) is identified in some maps as "Beckley", but in others as "Raleigh C.H." or Raleigh Court House. Beckley is the county seat of Raleigh County. Some of these smaller communities consisted of not much more than a courthouse during the 1860s.[50]

- ^ One source says Crook's infantry moved through Wyoming Court House.[49] However, a map from the same source does not show movement in Wyoming County, and Crook does not mention Wyoming Court House in his report.[52] The 5th West Virginia Cavalry camped at Wyoming Court House on May 5 before it joined Crook a few days later at a camp less than nine miles (14 km) from Dublin.[53]

- ^ Beginning in the 1840s in the United States, electric telegraph infrastructure was often placed along railroad lines.[62] During the American Civil War, the telegraph allowed unprecedented communication among military leaders.[63]

- ^ Although the Virginia Central Railroad had begun construction of railroad line further west, its line was completed only as far west as its Jackson's River Station.[64] Breckinridge had two railroad options to get to Staunton: 1) the Virginia Central railroad could be used from its western-most depot, the Jackson River Depot in Allegany County, to move east to Staunton; and 2) the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad could be boarded (Dublin Depot near New Bern, Wytheville, or Christiansburg) to move east to Lynchburg, where one could connect to another railroad that connected with the Virginia Central Railroad to the north at Charlottesville east of Staunton.[65]

- ^ Although communications from Breckinridge indicate that McCausland was to proceed to Staunton via the Jackson River Depot of the Virginia Central Railroad, McCausland moved to Dublin where his troops would use the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad to begin their trip to Staunton.[70]

- ^ Cozzens incorrectly calls the turnpike the "Dublin-Petersburg" Turnpike, while Duncan and Boyd Jr et al. (in a map) call it the "Dublin-Pearisburg Turnpike".[76]

- ^ In his report, Crook said "Had I but 1,000 effective cavalry none of the enemy could have escaped."[102]

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Ulysses S. Grant". American Battlefield Trust – Civil War Trust. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ Whisonant 2015, p. 80

- ^ a b O'Donnell 2024, p. 123

- ^ a b Cozzens 1997, para.4

- ^ Johnston II 1957, p. 310

- ^ Whisonant 1997, p. 31

- ^ Whisonant 2015, p. 162

- ^ Whisonant 2015, p. 155

- ^ Whisonant 2015, pp. 156–157

- ^ "New Market". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on December 16, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c Duncan 1998, p. 44

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 43–44

- ^ a b c d Whisonant 1997, p. 33

- ^ O'Donnell 2024, p. 122; Duncan 1998, p. 43

- ^ a b c Whisonant 1997, p. 30

- ^ Whisonant 1997, p. 29

- ^ a b Duncan 1998, p. 79

- ^ Johnston II 1957, pp. 310, 312

- ^ Whisonant 2015, p. 80; Johnston II 1957, p. 312

- ^ Whisonant 2015, p. 157

- ^ Boyd Jr et al. 2019, p. 71

- ^ Whisonant 1997, pp. 29–30

- ^ a b Breckinridge 1891, p. 719

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.5

- ^ Whisonant 1997, p. 32

- ^ O'Donnell 2024, pp. 122, 125

- ^ a b "Averell's Raid". e-WV, The West Virginia Encyclopedia - West Virginia Humanities Council. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ Scammon 1889, p. 941; Jones 1889, p. 946

- ^ Crook 1891, p. 9

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.2

- ^ a b c d Crook 1891, p. 10

- ^ "George Crook". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on August 22, 2024. Retrieved August 22, 2024.; Duncan 1998, p. 44

- ^ "Presidents and Politicians: The 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 30, 2024. Retrieved June 30, 2024.; Cozzens 1997, para.10

- ^ Crook 1891, p. 10; "Presidents and Politicians: The 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 30, 2024. Retrieved June 30, 2024.

- ^ Crook 1891, p. 10; "West Virginia History - Gray Forces Defeated in Battle of Lewisburg". West Virginia Department of Arts, Culture and History. Archived from the original on August 13, 2024. Retrieved August 13, 2024.

- ^ Reader 1891, p. 243

- ^ O'Donnell 2024, p. 56

- ^ McMullin 1891, p. 38

- ^ a b Duncan 1998, p. 48

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 53, 55

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 56

- ^ Lowry 2016, pp. 13–14, 16

- ^ a b c Browne 1891, p. 52

- ^ McCausland 1891, pp. 46–47, 49; "Confederate Virginia Troops - Bryan's Company, Virginia Artillery (Bryan Artillery)(Monroe Artillery)". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on August 23, 2024. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Dickenson 1891, p. 60

- ^ a b Jones 1891, pp. 56–57

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.19

- ^ O'Donnell 2024, p. 122

- ^ a b Duncan 1998, p. 45

- ^ "Appomattox Court House - Frequently Asked Questions". National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 25, 2024. Retrieved July 16, 2024.; "West Virginia History OnView - Courthouse, Beckley, Raleigh County, W. Va". West Virginia University West Virginia & Regional History Center. Archived from the original on August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 45–46

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 49; Crook 1891, p. 10

- ^ Reader 1891, p. 241

- ^ Breckinridge 1891, p. 719; "Dublin Historic District Pulaski (County)". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original on August 23, 2024. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 34–35

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 35–36

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 38

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 41

- ^ Withers 1891, p. 707

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 42

- ^ a b Cozzens 1997, para.8

- ^ "The Train and the Telegraph". Hagley Museum and Library (Smithsonian Affiliate). February 25, 2021. Archived from the original on July 18, 2024. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ^ O'Donnell 2024, p. 124

- ^ "History of the C&O Railway". Chesapeake and Ohio Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 17, 2024. Retrieved August 23, 2024.

- ^ O.N. Snow & Co., Thomas Crow & Co. (1861). New County Map of Virginia (from U.S. Library of Congress) (Map). New York City: O.N. Snow & Co. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ Breckinridge 1891, pp. 718–719

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 47

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 47–48

- ^ Jenkins 1891, p. 721

- ^ Breckinridge 1891, pp. 718–719; McCausland 1891, p. 44

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.17

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 52–53

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 53

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 55

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.18

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.18; Duncan 1998, p. 52; Boyd Jr et al. 2019, p. 72

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 55; McCausland 1891, p. 44

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 55–56

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 54–56

- ^ Smith 1891, p. 66

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 48, 50

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 56–57; McCausland 1891, p. 45

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 56–57

- ^ a b c d Duncan 1998, p. 58

- ^ a b Sickel 1891, p. 25

- ^ a b Reader 1891, p. 242

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.29

- ^ a b c d e f Duncan 1998, p. 59

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.30–31

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.30

- ^ Johnson 1891, p. 22

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.32

- ^ Beckley 1891, p. 54

- ^ Beckley 1891, pp. 54–55

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.34

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.35

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.37–38

- ^ a b c Duncan 1998, p. 60

- ^ a b c d Duncan 1998, p. 61

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 61; Dickenson 1891, p. 61

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 61–62

- ^ a b Crook 1891, p. 11

- ^ Smith 1891, p. 66-67

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 64

- ^ Douthat 1891, p. 58

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 64; Douthat 1891, p. 58

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 65

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 66

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 67

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 67–68

- ^ Boyd Jr et al. 2019, p. 77

- ^ Whisonant 1997, p. 36

- ^ a b Whisonant 1997, p. 37

- ^ Duncan 1998, pp. 69–71; French 1891, p. 64

- ^ Cozzens 1997, para.50; Boyd Jr et al. 2019, p. 76; Duncan 1998, p. 62; Whisonant 1997, p. 34

- ^ McCausland 1891, p. 44

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 63

- ^ Whisonant 1997, p. 39

- ^ Crook 1891, pp. 13–14

- ^ a b c Cozzens 1997, para.50

- ^ Crook 1891, p. 13; Reader 1891, p. 243; McCausland 1891, p. 45

- ^ McCausland 1891, p. 49

- ^ McCausland 1891, p. 45; French 1891, pp. 63–64

- ^ "the Wilderness - Spotsylvania and Orange Counties, VA - May 5–7, 1864". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Duncan 1998, p. 72

- ^ "the Wilderness - Spotsylvania and Orange Counties, VA - May 5–7, 1864". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on September 28, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2024.; Sheehan-Dean 1997, pp. 265–266

- ^ Sheehan-Dean 1997, p. 266

References

[edit]- Beckley, Henry M. (1891). "Report of Lieut. Col. Henry M. Beckley...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 54–55. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved July 27, 2024.

- Boyd Jr, C. Clifford; Whisonant, Robert C.; Herman, Rhett B.; Stephenson, George C.; Montgomery, Sarah B. (June 2019). "Geophysical and Archaeological Investigations of a Civil War Gun Emplacement in Pulaski County, Virginia". Archeological Society of Virginia Quarterly Bulletin (America: History and Life with Full Text). 74 (2). West Point, Virginia: EBSCO: 71–84. Archived from the original on July 8, 2024. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- Breckinridge, John C. (1891). "May 5, 1864, Correspondence of John C. Breckinridge". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 718–720. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- Browne, William H. (1891). "Report of Col. William H. Browne...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 52–53. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- Cozzens, Peter (October 1997). "Fire on the Mountain (cover story)". Civil War Times Illustrated (ProQuest). 35 (5). Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: EBSCO: 60–73. Retrieved July 7, 2024.[permanent dead link]

- Crook, George (1891). "Report of Brig. Gen. George Crook...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 9–14. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved June 23, 2024.

- Dickenson, Crispin (1891). "Report of Capt. Crispin Dickenson...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 60–61. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- Douthat, Henry C. (1891). "Report of Capt. Henry C. Douthat...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 58. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved July 31, 2024.

- Duncan, Richard R. (1998). Lee's Endangered Left: The Civil War in Western Virginia, Spring of 1864. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. OCLC 940541407.

- French, William H. (1891). "Reports of Colonel William H. French...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 62–64. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved August 2, 2024.

- Jenkins, A. G. (1891). "Correspondence of Brigadier General A. G. Jenkins". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 721–723. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- Johnson, Daniel D. (1891). "Report of Col. Daniel D. Johnson...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 21–22. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- Johnston II, Angus J. (August 1957). "Virginia Railroads in April 1861". Journal of Southern History. 23 (3). Rice University: 307–330. doi:10.2307/2954883. JSTOR 2954883. Archived from the original on July 12, 2024. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- Jones, Beuhring H. (1891). "Report of Col. Beuhring H. Jones...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 56–58. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved June 28, 2024.

- Jones, Samuel (1889). "Reports of Maj. Gen. Samuel Jones...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 945–947. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- Lowry, Terry (2016). The Battle of Charleston and the 1862 Kanawha Valley campaign. Charleston, West Virginia: 35th Star Publishing. ISBN 978-0-96645-348-5. OCLC 981250860.

- McCausland, John (1891). "Reports of Col. John McCausland...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 44–49. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- McMullin, James R. (1891). "Report of Capt. James R. McMullin...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 38. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- O'Donnell, Patrick K. (2024). The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln's Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby's Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America's Special Operations. New York City: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 978-0-80216-286-1. OCLC 1415847067.

- Reader, Frank S. (1891). History of the Fifth West Virginia Cavalry. New Brighton, Pennsylvania: Daily News, Frank S. Reader, editor and Prop'r. OCLC 1336164695. Archived from the original on July 14, 2024. Retrieved July 14, 2024.

- Scammon, E. Parker (1889). "Report of Brig. Gen. E. Parker Scammon...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 941. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- Sheehan-Dean, Aaron (1997). "Success Is So Blended with Defeat - Virginia Soldiers in the Shenandoah Valley". In Gallagher, Gary W. (ed.). The Wilderness Campaign: Military Campaigns of the Civil War. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 257–287. ISBN 978-0-80783-589-0. OCLC 1058127655.

- Sickel, Horatio G. (1891). "Report of Col. Horatio G. Sickel...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 23–28. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- Smith, D. Howard (1891). "Report of Col. D. Howard Smith...". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. pp. 66–68. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved June 27, 2024.

- Whisonant, Richard C. (November 1997). "Geology and the Civil War in Southwestern Virginia: Union Raiders in the New River Valley, May 1864" (PDF). Virginia Minerals. 43 (4). Charlottesville, Virginia: Commonwealth of Virginia, Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy: 29–39. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- Whisonant, Robert C. (2015). Arming the Confederacy: How Virginia's Minerals Forged the Rebel War Machine. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-319-14508-2. OCLC 903929889.

- Withers, John (1891). "May 4, 1864, Correspondence of John Withers, Special Orders No. 102". In Scott, Robert N. (ed.). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Series I Volume XXXVII Part I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 707. OCLC 318422190. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Shenandoah Valley Campaign March-November 1864 - Center of Military History, U.S. Army

- Recent photos of battlefield - flickr

- Battle of New River Bridge - Virginia Tech

- V&T RR During the Civil War - Encyclopedia Virginia